In October, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said that the U.S. can “absolutely” afford to financially support both Israel and Ukraine in their respective war efforts. Why is it the case that the U.S. can always afford to spend on war and the destruction of innocent lives, but when it comes to spending on vital public services that would benefit the majority of Americans or to tackle the most pressing challenges facing society, like climate change, they ask “how will we pay for it”?

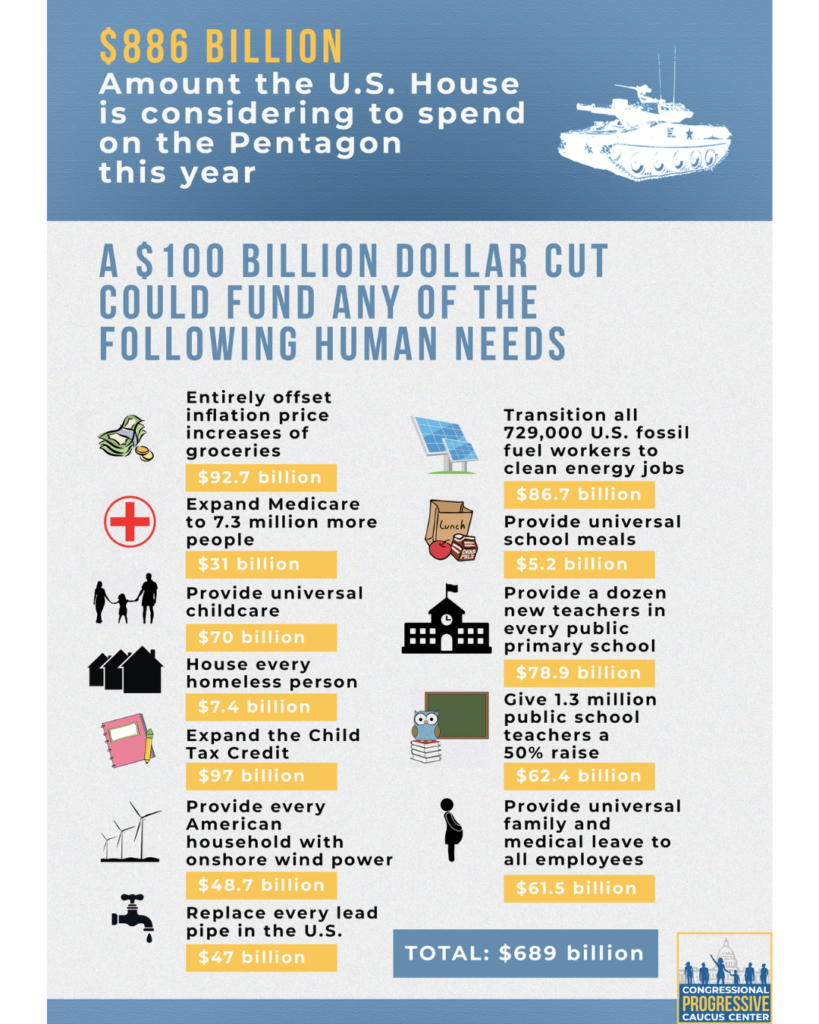

It doesn’t make sense that on the one hand the government claims it needs to cut spending because the federal deficit is too large, but on the other hand it consistently has seemingly endless coffers of money for the military, weapons manufacturing and by extension for war. Just this year, the US government passed the $886 billion National Defense Authorization Act, a $28 billion increase from fiscal year 2023 — a bill that Senator Bernie Sanders and few others voted against, highlighting that the U.S. could cut the bloated Pentagon budget and instead prioritize investment in healthcare, education, housing, climate action, and more. But of course, cuts to the defense budget were never on the table.

THE GOVERNMENT IS NOT A HOUSEHOLD

We have all noticed that when the government increases the Pentagon’s budget every year or spends billions on defense contracts with weapons manufacturers, concerns about public debt or deficit don’t seem to apply, and no one asks where all that money will come from.

That’s because asking “how will we pay for it?” is more of a political question — one that has been weaponized by some policymakers time and again — and an indicator of political motivations than an actual constraint. And questions about cutting the U.S’s deficit only make sense in the first place if we think of government finances like we do household finances.

This is the lie that we have been sold: that a government is like a household and so it must live within its means and balance its budget. If the government spends more than it takes in, its debt will balloon and become unsustainable, at which point the nation will go broke, much like you or I would go broke if we took on more debt than our income could sustain.

Authors and experts on this subject Frank Van Lerven and Andrew Jackson wrote a blog for Positive Money UK summing up why the household analogy is so dangerous:

“The familiar logic of the household analogy has become so embedded into public life that spending proposals that would help tackle some of our most pressing challenges – climate change, the housing crisis, unsustainable household debt – can barely make it out of the door. All too often, such proposals are stopped in their tracks by rival politicians and the media asking where the money is going to come from.”

This is relevant for the U.S. too. The self-imposed debt ceiling limit is a clear example of how the household analogy keeps popping up and why it can have dire consequences for both people and the planet. When the debt ceiling debate was shaking out earlier this year, former speaker of the House Kevin McArthy said,

“What I really think we should do is treat this like we would treat our own household. If you had a child, you gave him a credit card, and they kept hitting the limit, you wouldn’t just keep increasing it.”

Unless Congress agreed to deep spending cuts on vital public services, some policymakers refused to raise the debt ceiling. The final deal also baked in the approval of the climate-wrecking Mountain Valley Pipeline, which you can read more about in our blog here. And now we are once again facing a potential government shutdown based on fights over what some in Congress consider spending levels that are too generous.

We must call a spade a spade: the constant call to balance the budget is merely a harmful tactic used by some policymakers to cut spending on critical social programs and services, and to thwart the kind of large-scale spending we need to tackle issues like climate change.

WHY WE SHOULD REJECT THE HOUSEHOLD ANALOGY

There are several reasons why this analogy is a fallacy. For instance, the government’s financial power is far greater than and not comparable to any individual household. As economics professor Golnaz Motie notes in this interview, even someone with the best credit score “is just one step away from destroying that credit score by losing their job or missing one payment. That’s not the case for the government.”

Another reason households are not like governments is that the government is backed by the Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank, which, through coordination with the government, could choose to lower interest rates thus making government ‘borrowing’ cheaper. Naturally this pathway is not open to households, who must deal with whatever interest rate the Fed chooses to set, as we are doing now.

The usual outcome of the household analogy is to cut government spending, or impose austerity measures. But, as outlined in by Van Lerven and Jackson, when a government cuts spending, its impacts reverberate throughout the economy and eat into the government’s own income (taxes). This is unlike when a household decides to spend less, which does not impact said household’s income and does not have serious ramifications for the wider economy.

Because government spending is such a big portion of all spending in the economy, cutting public spending can lead to a fall in employment and wages in the public sector and in sectors that provide goods and services to the government, which could ultimately deplete tax revenues. Known as the ‘multiplier effect’, “by cutting its spending the government also ends up reducing its own income. So unlike a household, government spending and income are not independent of one another.”

Moreover, as noted in this article, attempts to drive down the public debt through austerity are unnecessary and can be incredibly harmful because U.S. government debt can actually provide a safe savings vehicle for many young people. So “trying to manage [the government like a household] merely impoverishes its population.”

Another key reason that governments are not like households is that the U.S. government is also able to issue its own currency, which you and I cannot do. That means that the U.S. also ‘borrows’ in its own currency, and as long as it does that it cannot go broke like a household.

HYPOCRISY IN PUBLIC SPENDING

The Biden Administration is seeking $105 billion to support both Israel and Ukraine, which according to Janet Yellen is “absolutely” affordable. To be clear, at least $14.3 billion would go towards enabling Israel’s occupation of and settler colonial crimes in Palestine. Yet, earlier this year, as 90 million Americans suffered through what might have been the hottest summer ever recorded, certain politicians came out in ardent opposition to spending on climate measures in Biden’s proposed 2024 budget.

And on the global stage, wealthy nations pledged to raise $100 billion by 2020 to help poorer countries adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change, known as loss and damage. This commitment, which includes the U.S., has not been met. The U.S. has failed to meet its commitments to the Global Climate Fund as well, the world’s largest multilateral climate fund. As author and reporter Kate Aronoff notes, the U.S. provides Israel with $3.8 billion in military aid annually, far outpacing America’s $3 billion commitment to the Global Climate Fund, to which the U.S. has only contributed $2 billion so far.

MOVING FROM ASKING “HOW CAN WE AFFORD IT?” TO “HOW CAN WE AFFORD NOT TO?”

What these examples make clear is that the question of public financing is more political than an actual monetary constraint. When the Coronavirus pandemic hit, President Biden treated the situation like the emergency that it was, spending $1.9 trillion into the economy to boost things like health care, education, and direct payments to families. This kind of response was a clear indication of the sheer financial power of the U.S. government and what it can achieve if targeted and spent on things the American people need most.

The question is why aren’t we treating the climate crisis or any of the other pressing issues we are facing with the same sense of urgency? Finance law professor Rohan Grey articulates the need for decisive action in an age of multiple overlapping crises — rising and rampant inequality, poverty, housing availability and affordability, healthcare, climate change, systemic racism are all issues that deserve to be treated as national emergencies the same way the COVID-19 pandemic was.

Professor Grey notes that in the response to COVID, the question we asked was not “how can we afford it” but rather “how can we afford not to?” With the climate crisis accelerating at an unprecedented scale and uprooting lives and livelihoods across America, this moment demands that we reframe how we think of government finances by doing away with the household analogy and asking instead: how can we afford not to?